Brain Injury Cases: First Steps and Advanced Tips

INTRODUCTION

It is difficult to define a “brain injury case” as a single construct. A brain injury may be defined as mild, having no positive radiological findings, no loss of consciousness and no measureable impairment. These cases will be particularly difficult to present to juries. Conversely, a brain injury that has been classified as severe, with positive imaging results, measureable impairment with obvious physical and/or behavioural, emotional or psychological deficits will generally present well to a jury. It is not enough to simply adopt the phrase “brain injury” when internalizing the case and when presenting it.

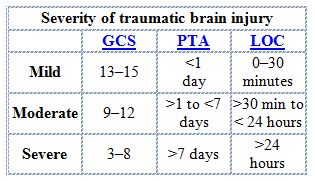

Brain injuries are rated as being mild, moderate or severe – or are expressed in a range of for example “mild to moderate.” The following table has been commonly used to classify brain injuries.

The terms brain injury and head injury are used interchangeably. However, I prefer to use the term “brain injury” as it is more descriptive, accurate and emotive. The case is not about the skull, which is what I think of when I think of the head. It is about the effects of the injury to the organ inside the skull. A mild traumatic brain injury is also referred to commonly as a concussion. Again, I do not like this term as it downplays the injury to the organ, and undermines its significance.

The implications of the brain injury must be understood by counsel in a critical way and presented in an analytical, strategic way. The presentation must be credible in that it is consistent with the anticipated evidence. Moreover, it must impart a theme to a jury in a way that makes sense and in a way that takes into account juror biases and belief systems.

In this paper, I will in turn consider basic first steps, and then more advanced techniques.

FIRST STEPS

First Things First: Is It a Brain Injury?

Identifying your client’s impairment as resulting from a brain injury may not be as easy one thinks. Mild traumatic brain injury can be (and almost always is) diagnosed differentially in the absence of any positive radiological signs. Perhaps the hallmark sign of mild traumatic brain injury (MTBI) or mild to moderate traumatic brain injury is the presence of cognitive impairment. Typically the signs and symptoms will consist of a host of difficulties with memory, focus, attention, word-finding, understanding and remembering information, difficulties in planning, prioritizing, making decisions…

Cognitive impairment does not necessarily equate with brain injury. While cognitive impairment does arise as a result of brain injury, it can also result from depression, illicit and/or medication use, generalized nonspecific pain disorder and/or malingering. It is critical to take the proper steps to determine what the impairments are and what they arise from. It may be from brain injury; it may not be.

It is not that one cannot present a case to a jury of a person who has suffered no brain injury but who has cognitive impairment as a result of dealing with chronic pain. The point is that one will not want to present the case as cognitive impairment resulting from brain injury when it instead results from another condition – equally deserving of compensation. If organic brain impairment cannot be established, do not use it as the basis for the claim. It may lead them to think you are making an untenable claim. You then run the risk of alienating the jury from accepting evidence dealing with issues other than causation. They might for example start to question whether your client is impaired at all, or whether he/she is disabled. Be guided by the nature and strength of the evidence you anticipate both parties will adduce before you theme the case and position it as one involving an organic brain injury.

Often, the experts will disagree on whether a person has suffered a brain injury. If the experts diverge on this issue, you must deal with it in an effective way at trial. How one deals with it depends on the extent to which the experts disagree. If both sides agree the person has impairment from the crash but the defence says it is all psychologically mediated, while the plaintiff claims it is organic, the safest option may be to say to the jury that they don’t have to even concern themselves with the issue of organic v non-organic. In this way, you will not have to put all your eggs in one basket.

You will obviously have to determine how strong the evidence is and how hard you want to push the organic brain injury theme. All things considered, I would prefer to present a physical organic injury to the brain causing the impairment than a non-organic cause. I suspect that a jury will be more accepting of the impairments where there has been a physical insult to the brain.

In summary, one must assess the strengths and weaknesses of the evidence to determine if the case is to be presented as an organic brain injury or not.

Theme the Case

Themes are the foundation of persuasion in a jury trial because they are a powerful device for controlling the manner in which the case is perceived.

A theme is a story that provides a concise statement of what the case is about. It creates a filter for the jurors to selectively receive evidence that fits with the theme and provides a mental shortcut for what the case is about. Jurors will be overwhelmed by the sheer volume of the evidence in any trial. A properly constructed theme will allow jurors to remember the evidence that is consistent with the theme and reject evidence that is inconsistent with it.

An effective theme is easy to understand, memorable and motivational. The opening statement is the first and most important opportunity to theme the case. Because plaintiff’s counsel goes first, they have the opportunity to position the case in a way that they want.

How does one come up with an appropriate theme? It really is a distillation of many factors. I engage in somewhat of an informal routine in developing case themes.

I become familiar with the medical evidence and non-medical evidence. I either read the discovery transcripts, or a summary of the transcripts. As well I consider how the client is likely to present at trial. In so doing, certain facts/issues will rise to the surface. It may be the client repeating the unending fatigue she feels affecting her mothering skills, and the despondency she feels from that. It may be the inability to interact with friends and family as before. Perhaps there was a particularly embarrassing moment for the client caused by cognitive dysfunction. These facts or issues will often be repeated by the client under questioning by doctors and counsel. As such, they become apparent and can be used in the development of a case theme. In searching for case themes, I am particularly sensitive to any poignant vignette I come across in the transcripts, the medical evidence, the lay witness statements or otherwise. For example, did the client express shame and embarrassment at forgetting the birthday of a loved one? I remember one client who had a brain injury who was a heavy smoker. He would often leave lit cigarettes unattended. I came across photographs of burn marks in the carpet and furniture. I then came across a photograph of the family dog Charlie – with a burn mark right between the eyes. I was able to use the image of that to create a theme of safety. Larry was not safe left unattended. He burned himself, his furnishings, his dog.

After reviewing the file material, I meet with the team of lawyers and clerks on the file and ask them to assist with finishing this sentence: “This is a case about…” It is not that a theme has to be captured in one sentence. However, it must be captured in as few words and ideas as possible. Simplicity is important. Think of it as the elevator speech. You have from the top floor to the lobby riding the elevator to explain to the jury what the case is about. The longer it takes, the less concise it becomes, the harder it becomes to understand and remember.

Focus groups can be an important tool in the theme development arsenal. You can test themes with the focus groups, or let them help you develop them. I consistently gain valuable information from members of the community about aspects of the case that motivates them, or alternately, that they are unable to accept.

There are many challenges in mild to moderate brain injury cases. It is harder to capture impairment that does not result from a purely physical cause such as a torn rotator cuff or fracture. Often impairment results from lack of motivation, change in behaviour, or emotionality. This is where story-telling becomes important. We often will use “before and after” vignettes to highlight the change in our client after his/her injury. A description of the changes can be captured in a theme. It should then be flushed out in a story.

A theme might go as follows:

Before the crash, Tricia was full of life, love and laughter. Now, she is morose, tired and depressed.

A story might go as follows:

Before this crash, Tricia spends her days working and playing. We will earn that Tricia works as an insurance adjuster. She gets up at 6:00 in the morning, gets her 3 year old son Ben ready for daycare and drops him off by 7:00. She commutes to work 50 kilometers every day. She starts at 8:00. She will work straight through until 3:30, usually having a quick lunch that she brings with her that she made that morning. After putting in a full day, Mommy drives the 50 km back home where she picks Ben up and plays with him when they get home. Tricia then prepares dinner for the family and they sit down to eat by 6:30. She then gets lunches and breakfast ready for the family for the next day. She might do a load of laundry and some light housekeeping. Her husband works long hours and childcare is primarily Tricia’s responsibility. And this routine lasts Monday to Friday. When the weekend comes, Tricia takes the opportunity to spend more time with Ben – taking him to the zoo, the Ex, visiting friends… Tricia also likes to take Ben to his grandparents on weekends. On one of the days, she must take time to do the household chores we all have to do – cleaning the house and doing the family’s laundry. By the time Tricia gets to bed at 11:30, she is tired and ready for a good night’s sleep.

Then the crash occurs – and the routine all changes.

Tricia no longer gets up at 6:00. She wakes up at 8:00 – in pain – always, and feeling unrefreshed. She forces herself to take Ben to his daycare. She returns home and lies on the couch, trying to get comfortable. Though she has no appetite and no interest in eating, she has some lunch. She attends physiotherapy and goes to a counselling session. She wants to learn how to better deal with the effects of her brain injury. She picks Ben up later in the day and sits him in front of the television and his iPad. As soon as her husband returns home, Tricia goes to bed, uninterested in engaging in conversation with anyone.

The story reinforces the theme of the change from the energetic, fun- loving Mom to a tired, hopeless, depressed mother in a way that promotes an understanding of the case. It is memorable and motivational. It thus captures the 3 important qualities of an effective case theme.

Use Lay Witnesses

Lay witnesses are so important because of the Identification Bias. This bias holds that people are more likely to be influenced by those they can identify with. We are more likely to identify with people we see as similar to ourselves. For this reason, lay witnesses take on increased relevance in jury trials.

How does one go about ascertaining the identity of possible lay witnesses?

This is really a collaborative effort. After examinations for discovery, we write to the client asking for names and contact details of friends, family, work colleagues, and those who we feel might have something relevant to offer. Clearly, witnesses who are unrelated to the plaintiff and are not seen as biased are preferable. We are interested in people who can assist in developing and promoting our theme. Have they witnessed a change in behaviour? If so, it is important to present examples. The examples will become mini-stories that can morph into the greater theme.

I am looking for witnesses who are relatively neutral (not close friends or family) and who have made observations that I feel will help persuade the jurors of a particular point. For example if the client is presented as having a memory impairment, use lay witnesses to provide salient observations regarding poor memory. If the issue is behavioural, use lay witnesses to provide particularly effective observations regarding behaviour. Did they witness the plaintiff, who was formerly even-keeled and mild- mannered lose his temper and yell at his young child?

One must be careful not to have lay witnesses being quoted (in Will Say statements) saying things that will have no credibility. From time to time I have to edit lay witness statements taken by our clerks. An example might be a friend or family member saying: “Lori can’t work anymore.” Or even “Lori is always in pain.” “Lori can’t enjoy life anymore.” If the lay witness provides a statement that goes beyond their observations, it will lose its persuasive value. As well, it is difficult to gauge just how much lay evidence is enough. My usual practice is to have a half a dozen or so witness statements. Then as the evidence is adduced at trial, I will cut back on the number of witnesses, depending on my feel for how the evidence is being received.

In summary, the value of lay witness evidence is rooted in the Identification Bias. Take steps to search for appropriate lay witnesses, ask the right questions, and limit their statement to matters they are able to make observations about.

Contrast the Before with the After

Presenting the post-crash life is usually easier than presenting the pre-crash life. It is more recent and many of the witnesses – particularly the expert witnesses – will have seen the plaintiff only after the crash.

Unless the jurors have an understanding of the plaintiff’s life before the crash, they will not appreciate how much he/she has changed.

Establishing the contrast can be done in your opening and in evidence you present at trial. An example appears above under the Theming the Case subsection.

Treatment and medication charts that cover both pre and post-crash time frame can be effective tools in front of a jury. This is particularly so for someone who visited the doctor and consumed medication rarely before the crash.

Photographs are another demonstrative tool to establish pre-morbid success, happiness and health. To the extent the photographs capture an activity, or a mood, they depict a story – which makes them persuasive.

A long-standing family doctor will be helpful in establishing a healthy (“normal”) pre-crash status.

Finally, lay witnesses, such as work colleagues, friends, sporting/recreational friends will help paint a pre-accident lifestyle picture.

In summary, it is not just establishing the present that is important in brain injury cases. It is important to highlight the change from the pre-morbid health and lifestyle to the present through demonstrative evidence, lay witnesses and family doctors.

Use of Demonstrative Evidence – Part 1

As noted above, use of treatment and medication schedules are useful in two ways. First, they document – at a glance – the treatment and medication the client requires as a result of the crash. Second, by contrasting this information with treatment and medication use pre-crash, it helps define the crash as the life-changing event. It is visual and helps to reinforce the theme.

A model of the brain is useful in presenting brain injury cases. I prefer a colour brain. I recommend using it in your opening and with different expert witnesses to reinforce the organic nature of the injury. A brain injury is somewhat mysterious to the lay person in that it involves an organ that no juror will have ever seen before. With leave of the judge, you can pass the model to each juror – describing such things as the weight, texture, complexities of the brain as they study it. You will be seen as an educator – trying to assist them in understanding the evidence. In this way, your credibility will be enhanced.

You can also use the brain to explain the mechanism of injury, whether it be coup-contra-coup or otherwise.

Another very effective way of explaining the mechanism of injury is through medical-legal illustrations, with radiographic inset if available

Be prepared to deal with radiographic evidence that fails to demonstrate any abnormality. Educate the jurors to understand that a normal x-ray does not mean there is no brain injury. Explain how the imaging techniques work and their limitations. You can explain that the doctor ordered the imaging out of a concern that there was a brain injury.

Finally, in preparing for trial in any brain injury case, I recommend that you attend the home of the plaintiff. I am often surprised at things I see. Frequently, I will see Post-It notes located strategically throughout the house to remind the plaintiff to do certain tasks, like brush their teeth, or lock the door. There might be calendars hung containing a litany of medical and rehabilitation appointments. Is there an automatic shut-off device on the stove? Be sure to bring along a camera and enter the photos as exhibits at trial.

In summary, demonstrative evidence can be helpful in providing the jurors with an understanding of how the brain works, how it was injured, and how it is now impaired. Be prepared to deal with negative radiological evidence. (The importance of inoculation is discussed below.)

ADVANCED TECHNIQUES

Retain a Neuropsychologist

Clinical neuropsychology is an applied science concerned with the behavioural expression of brain dysfunction .

I recommend retaining a neuropsychologist in every case involving impairment of cognitive function.

The neuropsychological assessment in any brain injury case – mild, moderate or severe – provides objective evidence of cognitive functioning – and cognitive impairment.

A properly conducted neuropsychological assessment consists of a clinical interview by a person with doctoral level training in brain and behaviour relationships, administration and interpretation of sophisticated, validated neuropsychological testing and a review of medical records. The testing results are to the neuropsychologist what the MRI is to a neurosurgeon. Although a well-qualified physician will be able to testify as to how he or she made a diagnosis of TBI as a result of applying his or her expertise to the complaints made by the plaintiff over time and the mechanism of injury, he or she lacks any real objective evidence to serve as a foundation for the opinion. Nonetheless, a physician will routinely make such a diagnosis in the absence of any objective data where none are available. Such diagnoses are made by physicians daily – for example in diagnosing headaches or stomach pain…

The advantage the discipline of neuropsychology lies in the valid, reliable, normed testing that has developed over the past 50 or so years.

It is a common suggestion of defence counsel that it is easy for a plaintiff to exaggerate or overstate his or her impairments – either consciously in order to enhance their potential damage award, or subconsciously, having “bought in” iatrogenically to others’ suggestions, or constituting a “cry of help.” (I would never want to rely on any of these reasons to explain why our clients test results were invalid.)

In fact, neuropsychologists will employ a battery of tests to determine the validity of effort. Moreover, several tests have internal validity checks for consistency of response. The neuropsychologists I employ know not to deliver a report for a client who fails validity testing. There is no apparent consensus among neuropsychologists on what conclusions can be drawn for a client who has completed the battery of tests but has failed validity testing on one or more measures. Some argue that any invalid test results invalidate the entire neuropsychological assessment, meaning no conclusions can be made. Others argue that conclusions can be drawn, but that the conclusions must be interpreted cautiously at best. I suspect a juror would not draw any conclusions favourable to your position regarding a client who has failed validity testing. For this reason, you should develop a relationship with the neuropsychologists you employ to avoid getting expensive reports that you will have to claim privilege for and absorb the cost of.

No one wants to think of their clients as malingerers or as persons not giving full effort. That said, most of us have had the unfortunate experience (better learned before trial than during) that we have had the wool pulled over our eyes. When scheduling a neuropsychological assessment, I send a letter to the client advising them of the lengthy (all day or 2 day) appointment and advise that they will spend the day completing a battery of tests. I stress the importance of trying their best, advising that the sophisticated testing is designed to detect those people trying to portray themselves as worse off than they are. The T.O.M.M. test in particular is so well designed, and so easy for a jury to understand, that failing such test makes it virtually certain that the report will have to be buried. I just don’t believe that a jury would accept invalid test results due to poor or inconsistent effort to be a “cry for help” as some neuropsychologists proclaim. I rather expect the jury would find it to be a “cry for money.”

The neuropsychological assessment is useful in the following respects:

1. It will provide a diagnosis and classification of the severity of brain injury. Alternatively, if brain injury is excluded from the diagnosis, it will provide other psychological diagnoses, such Pain Disorder Associated with Psychological Factors and a General Medical Condition and Adjustment Disorder with Mixed Anxiety and Depressed Mood.

2. It will establish the collision caused the diagnosed injuries/disorders.

3. It will assess the level of neurocognitive impairment overall (generally mild, moderate or severe).

4. It will provide a detailed assessment of the level of impairment of individual neurocognitive functions such as:

– Information processing speed

– Information processing accuracy

– General cognitive proficiency

– Working memory

– Simple and complex attention capacities

– Sustained attention

– Susceptibility to proactive interference and retroactive interference

– Auditory memory performance

– Visual memory performance

– Executive functions including several complex abilities including the formulation, planning, execution, sequencing and evaluation of goals

5. It will provide an opinion on ability to work.

6. It will provide an opinion on ability to function.

7. It will provide recommendations for treatment.

I will circulate a supportive neuropsychological assessment to the treatment team and request that the recommendations be discussed with the family doctor, and be implemented where possible.

I generally do not ask the accident benefits insurer to fund the assessment. I want to control the process and be able to bury the report if need be. This can sometimes cause difficulty for the case manager who recommends in team meetings that a neuropsychological assessment be undertaken and is instructed by me not to let the insurer – or others know that an assessment is being done in the tort action. You have to stickhandle the situation best as you can.

In summary, the neuropsychological assessment is an important tool in your arsenal for establishing a diagnosis, causation, and impairment of neurocognitive function. Well validated testing established in the discipline of neuropsychology provides a logical basis for advocating (where it is in one’s best interest to so advocate) that the evidence of a neuropsychologist is superior to the opinion evidence of a mere physician.

CONDUCT A SITUATIONAL ASSESSMENT

I have recently begun to use the Activities of Daily Living Situational Assessment (“Situational Assessment”) for clients with acquired brain injury. I have found it to be a very effective way of presenting impairments my brain injured clients have in everyday living that is easily understood by judges and jurors alike.

The Situational Assessment is akin to the Functional Capacity Assessment for assessing functional physical capacity in that it tests performance in a way which can be extrapolated to real world function.

The situational assessment provides a bit of a foil for the neuropsychological assessment. As noted above, a strength of the neuropsychological assessment is the science that lies behind the testing. It is perhaps equally a weakness – that the jury may become overwhelmed by the science where opposing neuropsychologists argue about the significance of say, certain of the raw test data. I recently conducted a trial where the evidence of 3 opposing neuropsychologists was given over several days – much to the chagrin of the jurors, whose eyes glazed over. Conversely, the strength of the situational assessment lies in its simplicity and use of real world tasks which requires little scientific rigour or analysis.

I have used the Situational Assessment across the full spectrum of brain injury severity. In each instance, the objective is the same – to demonstrate that the plaintiff has a compromised ability to safely and effectively engage in activities of daily living. This in turn can be used as evidence to support any number of claims, but particularly attendant care and future care cost claim, such as RSW, cognitive remediation, and occupational therapy costs.

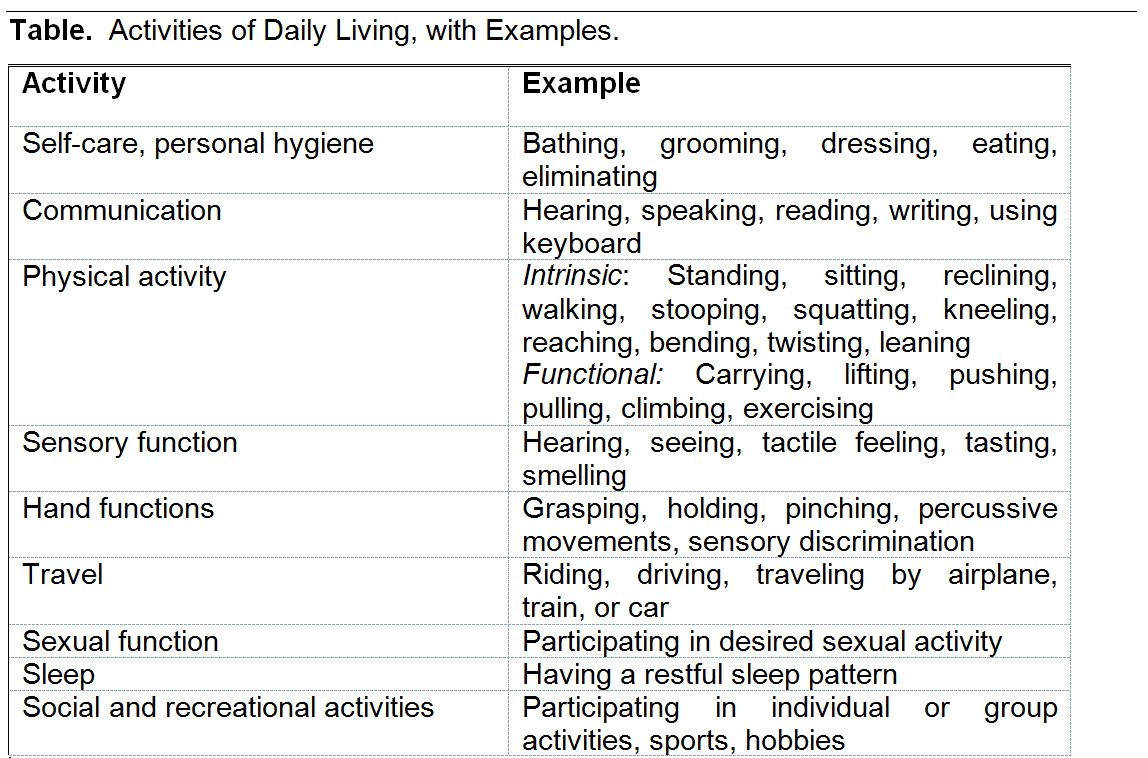

Activities of Daily Living can be defined in any number of ways. A facility experienced in conducting such assessments will provide its own definition. It is important to use a definition that is not restricted to very basic routine physical activities such as bathing and brushing one’s teeth. For such an example, see the Table “Activities of Daily Living” contained in the AMA Guides to the Evaluation of Permanent Impairment at p. 317.

Such a definition does not allow for assessment of more complex ADLs such as shopping, meal preparation, taking phone calls from strangers, engaging in multi-tasking….

Marg Ross, of Ross Rehabilitation & Vocational Services, an experienced assessor uses a more general definition. Ms. Ross comments:

For the purposes of the assessment, Activities of Daily Living are defined as Routine activities carried out by an individual every day or habitually in various environments. These are activities suited to giving the person individual autonomy by ensuring his or her personal survival and his or her maintenance within the community. Such activities are indispensable to the survival of the individual and others are related more to socialization.

ADLs are grouped according to three domains as defined in the ADL profile:

1. Personal, which includes activities related to personal care such as hygiene, dressing, eating, and health maintenance;

2. Home, which includes activities typically carried out in the home such as meal preparation and household maintenance; and

3. Community, which includes activities related to the social functions of the person such as transportation, outdoor mobility, use of public services, including shopping, and time management including keeping appointments.

Thus, the ADL Situational Assessment is a systematic performance-based measure of function, done in a manner that targets deficits known to impact on long term independence for clients with ABI. There are multiple activities that have been developed for the purposes of an ADL Situational Assessment. To illustrate, the meal preparation task will be briefly described. For the purposes of this activity, the client is oriented to a Situational Assessment Centre, including the kitchen. They are then presented with a scenario in which they are required to prepare a two-course hot lunch for two by a certain time. They are advised that the evaluator is only there to observe and they are to work as independently as possible. They are then given the same instructions in writing with a twenty-dollar bill. In order to accomplish the goal, the client will need to engage in multiple tasks in the assessment centre and surrounding community.

The client then has to plan the meal, transport themselves to a grocery store, shop for groceries, purchase the groceries, transport themselves to the assessment centre, and make the meal – all within a scheduled time frame.

There are any number of tasks which might be given by the assessors, which will be guided by the impairments documented in the file. Other tasks will include answering a telephone and taking messages, completing a budgeting exercise, performing cleaning and housekeeping activities, and engaging in a community outing.

Once testing is completed, the assessor will document the individual’s level of performance impacting ADL function, noting that such function is impacted by emotional tolerance, behaviour, cognitive function and physical tolerances.

The opinion takes on a “real world” persona given the “real world” testing conditions.

By way of example, l referred a lady who had suffered a moderate brain injury and complex pelvic fracture in an accident. After undergoing a situational assessment, the assessor noted:

As outlined above, Ms. Smith is disabled from engaging in her ADL tasks including personal care, meal preparation, and community mobility, shopping, finances and appointments. Ms. Smith will require continuous supervision and attendant care (24/7 care) due to her cognitive limitations (executive functioning and mental fatigue), physical limitations (unsafe, slow and inefficient mobility, exacerbation of left-sided hemiplegia and spasticity, poor balance, physical fatigue), and emotional and behavioural difficulties (irritability, agitation, outbursts, distress, poor insight, resistance to prompting).

In summary, consider an ADL Situational Assessment whenever the client and/or the client’s family feel the client has difficulty in performing some ADLs, whether routine, or, more complex ADLs. A Situational Assessment is persuasive and establishes impairment and the need for supervisory and other care.

USE OF IMAGING

Moderate to severe traumatic brain injury will most likely involve positive imaging through CT scans, MRI or otherwise. More recently however, single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) scans and functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) are available to demonstrate abnormalities in the brain.

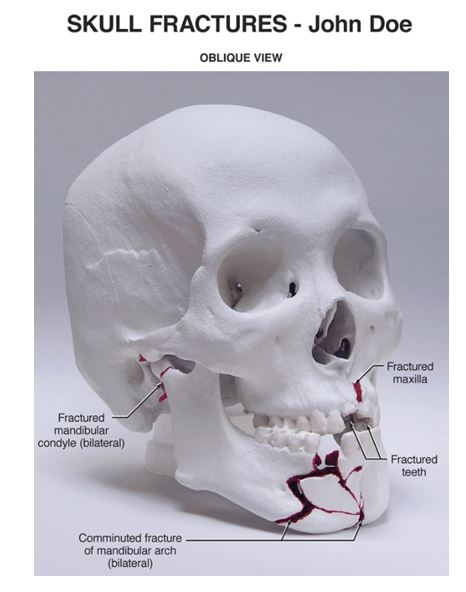

Below is a photo of a Rapid Prototype Model of the skull. This is a customized 3D print generated from CT scans. This image shows facial fractures, but work is underway to apply this technology to printing TBI findings in 3D to ‘see inside’ the brain.

A SPECT scan is a type of nuclear imaging test that creates 3-D pictures. It can show how blood flows through your brain and what areas of your brain are more or less active than other parts.

A fMRI is a functional neuroimaging procedure using MRI technology that measures brain activity by detecting associated changes in blood flow. It is a non-invasive technique which does not involve radiation.

Cognitive deficits following a mTBI usually occur on measures of attention, memory and processing speed (which can be identified in most cases through neuropsychological evaluation.) Further, depression is a significant concomitant of mild TBI, with Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) occurring in one quarter of such patients. Not surprisingly, persisting cognitive deficits and disturbed mood are associated with poorer long-term outcome.

Functional neuroimaging has consistently shown abnormalities in prefrontal regions in mTBI, which are associated with cognitive deficits. fMRI activation is attenuated in mTBI patients when completing complex tasks, such as involving working memory. Studies measuring resting-state fMRI in mTBI show decreased activity at rest following TBI compared to healthy controls. Cerebral perfusion measured via SPECT shows hypoperfusion (decreased blood flow) in frontal areas of the brain associated with lower neuropsychological test scores. Thus, use of such technology can assist in correlating the clinical findings of the examiner with imaging results. Imaging is impressive as a visual demonstrative tool.

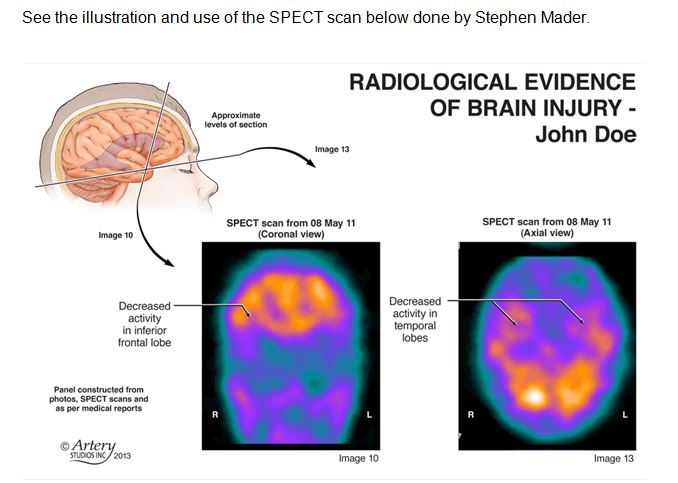

Stephen Mader is Canada’s pre-eminent medical illustrator. See the illustration he has prepared regarding the SPECT scan. Illustrating SPECT scan images is very sophisticated and challenging. It involves consultation between the illustrator and the neuroradiologist. The imaging can be made an Exhibit and used by the expert witness (neuropsychologist, neurologist and specialized physiatrist) as an aid in providing their evidence. With leave of the judge, it can be referenced in your opening, and form part of your closing argument. A medical illustrator can make the actual SPECT or fMRI more jury friendly. The objective is to use the illustration and imaging as an anchor for the injury by establishing a link between the functional impairment and the visual image of the affected area of the brain .

See the illustration and use of the SPECT scan below done by Stephen Mader.

One word of caution of the use of fMRIs and SPECTs in establishing mTBI. Notably, many of the regions of the brain affected by TBI are also associated with Major Depressive Disorder without comorbid TBI. That is Major Depressive Disorder in general is also associated with frontal hypoperfusion on SPECT scans, decreased activation during cognitive task performance and alterations in resting-state activity. Thus, it is unclear from a clinical standpoint whether decreased cerebral activity following mTBI may be attributed to neurological insult or depression. The expert witness will have to deal with the differential diagnosis in his or her testimony.

In summary, consider arranging a SPECT scan or fMRI in a case which has not yielded any positive imaging results. Such tests can usually be done privately at a hospital in about 10 days at an approximate cost of $1,000. Used as an aid in and of themselves, and in conjunction with a good medical illustrator, they can be effective in correlating clinical findings with imaging techniques in a helpful, visual way.

INOCULATION

Inoculation is the process of acknowledging a potential area of weakness or controversy in the evidence, and giving the jury a way of dealing with it in a way that is not harmful to your case.

By using inoculation, you will appear to be fair-minded to the jurors. Inoculation removes the sting of a particular point if it first comes from you and not the defence. Critically, it reduces resistance to your case.

Obvious areas of weakness to a typical mTBI case include the following:

1. Your client looks perfectly healthy.

2. There is a lack of radiological evidence.

3. There is a lack of other objective evidence.

Counsel are wise to acknowledge these issues at the outset and to inoculate against them in your opening and in the evidence of the witnesses.

It is my belief that the public – and hence our jury pool – has become much better educated and more accepting of the adverse implications of a mTBI through the notoriety of sports injuries – and in Canada particularly concussions in the sport of hockey. The public has been besieged with images of hockey players laying prone on the ice, unconscious, or trying to get back on their feet. The concept of multi concussion syndrome is well known and accepted. Hockey players look healthy. The point is there is less resistance to the usual defence arguments than formerly. But you are wise not to take it for granted.

In examining your experts, you may wish to start with this question:

“Dr. Expert, when John Smith went to see you, did he look healthy to you?” In this way, you are seen as meeting the issue head on and will have effectively inoculated against it.

In summary, be vigilant to inoculate against the usual defence arguments in a mTBI case. It will take the sting out of the defence arguments and will reduce resistance to your case.

CONCLUSION

Brain injury cases run the gamut from mild to severe. The greater challenges lie in the mild to moderate brain injury. As with all trials, the presentation of a clear, effective, motivational theme is critical. Counsel are well advised to take whatever time is required to develop a theme that is consistent with the anticipated evidence – and with the presentation of the plaintiff. It is important to lead evidence to create a credible, likeable plaintiff whom the jurors are motivated to help. Be strategic when presenting the case and use demonstrative evidence to your advantage.

Written By

Born and raised in Brantford, Ontario, Jim Vigmond is Oatley Vigmond’s founding and managing partner. Brought up in a hardworking Canadian family, Jim’s work ethic was instilled in him by his parents. His father was a tool and die maker turned teacher; his mother, a retail store manager. Jim’s father built their family home himself, and both his parents believed in setting an example for their children defined by humility, hard work and integrity. Jim attributes his ability to connect with his clients to the fact that many of them come from similarly modest backgrounds. “There’s no filter needed when you’re dealing with me,” says Jim. “I am who I am.”